Section 2: Laying the foundations – Option definitions

**📚 Prerequisites:** If you’re new to options trading, start with our Complete Guide to Trading Options on Deribit for a comprehensive overview before diving into derivatives contracts.

Lecture 2.1: An introduction to derivatives contracts

Firstly, it’s important to lay down a base level of knowledge. This is to make sure you understand what is being talked about later in the course when we start moving into the more intermediate and advanced topics.

There is a fair amount of terminology to learn with options so this section will be a little definition heavy. Stick with it though, and don’t worry if you can’t quite visualise how everything connects together yet, because we will be going into much more detail and coming back to these definitions in later sections.

Trading an asset directly

The most basic form of trading is buying and selling an asset directly. This asset could be real estate, another currency, gold and silver bars and coins, stocks and shares, or even new digital assets such as bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. When trading an asset directly, you will exchange the currency or asset you already own, for another.

For example, you may have some dollars and wish to purchase some bars of silver. You may wish to do this because you expect these silver bars to appreciate in value. You will go to a silver bullion dealer, pay them your dollars, and they will give you your shiny new bars of silver. You now own and possess the silver bars, and no longer own or possess the dollars you used to pay for them. You have exchanged the dollars for the bars of silver in a single transaction, with no further rules or obligations.

What is a derivative?

A derivative is a contract that derives its value from an underlying asset. This underlying asset could be silver for example. It allows traders to speculate on the price of the underlying asset, without having to buy or sell the asset itself.

A derivative contract can take several different forms, for example a futures contract, or an options contract. Whatever the details though, a derivative contract is a legal agreement between two parties to buy or sell some underlying asset, according to the parameters laid out in the contract.

In our previous example you purchased some silver directly, and in doing so you would benefit from any subsequent increase in the price of silver. It is possible to get this same exposure to the price of silver without purchasing the silver itself though. This can be done by utilising a derivative contract that derives its value from silver. Silver here being the underlying asset.

For example, let’s say silver is trading at a price of $20/oz and you were considering purchasing 10,000 troy ounces of silver. To purchase the silver directly you would need to pay the bullion dealer $200,000 (plus any premium which we’ll come on to shortly), then either store the 10,000 ounces with a company that handles storage, or take physical delivery of the 10,000 ounces yourself.

If the price of silver then increases to $30/oz, you can sell the 10,000 ounces for $300,000, and so will have made a profit of $100,000.

However, you could use a silver derivative contract instead of purchasing the silver directly. You’ll still be able to make the same profit (or likely even better as we’ll discuss), but with several key benefits.

A futures contract is an example of a derivative contract you could use. By purchasing a silver futures contract, you are not purchasing the silver itself, but you are entering into a legal agreement to purchase the silver at some future date. These futures contracts will track the price of the underlying asset, which in this case is silver. You are free to sell this futures contract before the contract expires to realise any profit (or loss) you’ve made.

The CME silver futures contracts for example represent 5,000 ounces of silver per contract. So, instead of purchasing 10,000 ounces of physical silver you could purchase 2 CME silver futures contracts. This would give you the same price exposure to 10,000 ounces that you wanted, but without the need to arrange storage. If the price of the silver futures contract then increases to $30/oz, you can sell the 2 futures contracts for $300,000, and so will have made a profit of $100,000.

A derivative is a contract that derives its value from an underlying asset. This underlying asset could be silver for example. It allows traders to speculate on the price of the underlying asset, without having to buy or sell the asset itself. Learn more about how derivatives work in options trading

So why would a trader prefer to use the derivative contract?

In our simple example you made $100,000 whether you bought the physical silver or used the silver derivative, so why would someone choose to use the derivative? Firstly, we ignored transaction costs in the example. In reality, the profit from purchasing the physical silver would likely be drastically reduced by several factors.

Physical silver often has a premium added on by the bullion dealer. Depending on which country you live in and how large the current demand for silver is, this premium could be anywhere from a few percent to 30%+. You may also have taxes to pay. In the United Kingdom for example there is 20% VAT to pay on top of the purchase price for physical silver.

In our example where you purchased 10,000 ounces at $20/oz for a total of $200,000, you could end up paying as much as $260,000 if the premium and taxes add up to 30%. If you then sold the silver for $300,000 as before, you would only make a profit of $40,000 instead of $100,000!

You will also have to worry about the cost of transporting the silver, as well as the cost of storing it. You can purchase a safe and store it yourself, which may cause security and insurance issues. Or there are companies that will store it for you, but this will come at an extra cost depending on how long you store it with them.

Using a derivative contract instead, in this case the silver futures contracts, avoids all these costs. The futures contract may be trading at a slight premium to the spot price, but this will normally be considerably lower than the premium for physical silver. There is also no cost to store or transport the futures contract. You simply hold it in your trading account until you wish to close the position.

Derivatives also add the possibility of using leverage which can be of huge benefit to traders when used correctly. When purchasing the physical silver you needed to send the full $200,000 to the bullion dealer. When purchasing the futures contracts though, your broker may allow you to purchase them with leverage. Even a modest amount of 2x leverage would allow you to gain the same price exposure to 10,000 ounces of silver with only $100,000 in your trading account. We will cover this in much more detail later in the course, so don’t worry if you don’t quite follow this point on leverage yet.

We have only looked at a single simplified example so far of course, but the take away in this first lecture is that derivatives contracts allow traders to structure trades that suit their needs, while also avoiding many of the disadvantages of purchasing physical assets.

Summary

In summary, a derivative contract allows a trader to gain exposure to price movements of an asset without having to buy or sell the asset directly. The value of the derivative contract will be in some way tied to the price of the underlying asset, according to the terms of the contract.

Trading the underlying assets directly can be expensive and inefficient. Derivative contracts solve these problems. In the case of option contracts, which we will move on to next, they even allow completely new trades to be executed that would simply not be possible trading the asset directly.

Lecture 2.2: Option contract parameters

In the previous lecture we covered what a derivative contract is. To recap briefly a derivative contract is a legal agreement between two parties. The contract derives its value from an underlying asset, according to the rules set out in the contract.

An option contract is a specific type of derivative contract. It gives the buyer of the option contract, the right to trade the underlying asset at a certain price on a certain date. The buyer is not obligated to exercise their right, but they have the option to, hence the name ‘option contract’.

When looking at an option contract there will be 5 main parameters to consider:

- The underlying asset – The asset that the option contract derives its value from. In the example in the previous lecture, this would be silver, but this can just as easily be bitcoin, another currency, or stocks.

- The option type – The two types of options are call options, and put options. A call option gives the buyer of the option the right to buy the asset at a given price, and a put option gives the buyer of the option the right to sell the asset at a given price.

- The expiry date – This is the date the option will expire and be exercised if it has any value. Exercising an option means the buyer exercises their right to buy or sell the asset.

- The strike price – The price at which the buyer has the right to trade the asset on the expiry date. For a call option the buyer has a right to buy the asset at the strike price, and for a put option the buyer has the right to sell the asset at the strike price.

- The option price (aka the option premium) – This is the price the buyer pays to the seller to purchase the option. In other words it is the premium the buyer pays the seller for the right to trade the asset at a specific price.

It’s important to understand the two different types of options, call options and put options. We will cover each in great detail in their own sections later in the course, but for now it is useful to know the main difference between the two.

The buyer of a call option, is purchasing the right (or option) to buy the asset at the strike price, on the expiry date.

On the other side of this trade of course is the trader who is selling this call option to the buyer. The seller of the call option, has an obligation to sell the asset to the call option buyer at the strike price, on the expiry date.

The buyer of a put option, is purchasing the right (or option) to sell the asset at the strike price, on the expiry date.

On the other side of this trade, is the trader who is selling this put option to the buyer. The seller of the put option, has an obligation to buy the asset from the put option buyer at the strike price, on the expiry date.

It is usually put options that confuse new option traders. This is because the buyer of a put option is actually betting on the price of the asset decreasing. Put options increase in value when the price of the asset goes down. Don’t worry if you don’t fully understand this yet, because there are two entire sections on call options and put options and exactly how each works.

For now just remember that a call option buyer has the right to buy the asset, and a put option buyer has the right to sell the asset.

Let’s look at how you may see an option written

On the Deribit platform you will see option instruments written in the following format:

Underlying Asset – Expiry Date – Strike Price – Option Type

For example if you see an option written as:

BTC – 30OCT20 – 13000 – C

This means the underlying asset is bitcoin (BTC), the expiry date is 30th October 2020, the strike price is $13,000, and the option type is a call. The buyer of this call option then, is purchasing the right to buy bitcoin at a price of $13,000 on 30th October 2020.

If you see an option written as:

BTC – 26MAR21 – 11000 – P

This means the underlying asset is bitcoin (BTC), the expiry date is 26th March 2021, the strike price is $11,000, and the option type is a put. The buyer of this put option, is purchasing the right to sell bitcoin at a price of $11,000 on 26th March 2021.

The final of the five parameters, the option price, will be displayed in the option chain and in the order book for each option. More on this later.

Lecture 2.3: European vs American options

We mentioned in the previous lecture that exercising an option means the buyer exercises their right to buy or sell the asset.

A call option is the right to buy the underlying asset. Exercising a call option, means the holder of the call option exercises their right to buy the asset at the strike price of the option.

A put option is the right to sell the underlying asset. Exercising a put option, means the holder of the put option exercises their right to sell the asset at the strike price of the option.

Options can further be categorised as either European or American style. The main difference between the two relates to when the option can be exercised.

American style options can be exercised at any time before expiration. For example, assume a trader holds an American style call option of stock XYZ with a strike price of $50. That means they have the right to buy XYZ for $50 per share. As the option is an American style option, they can exercise that right at any point they choose before the option expires. In doing so they will then buy the stock at a price of $50 per share. So if the share price increased to $70 for example, the trader could exercise their $50 call option and buy the stock for $50 instead, saving $20 per share compared to buying the stock at the current market price.

European style options are only exercised at the moment they expire. For example, imagine the same stock and option as before, but this time it’s a European style call option of stock XYZ with a strike price of $50. They still have the right to buy XYZ for $50 per share, but because the option is European style, they cannot exercise this right until the moment of expiration. So if the share price increased to $70 before expiration as before, the trader cannot immediately exercise the option and buy the stock for $50 per share.

You may be thinking, why would someone choose to trade European options if they are forced to hold the option to the expiry date. This is a very common question of traders new to European options. The answer is that the option buyer is not forced to hold the European option to expiry. While they cannot exercise the option early, they can simply sell the option back to someone else. This will close their position and bank the profit. Doing this will normally result in a larger profit than exercising would have done anyway, due to something called extrinsic value.

Continuing with the European example, if the price of XYZ has increased to $70 but with time remaining before expiration, the European option buyer cannot exercise the option to buy XYZ at $50 per share yet. However, what they can do is sell the option to someone else. The value of this $50 call option will also be higher than the $20 difference between the $70 share price and the $50 strike price of the option (due to the extrinsic value we mentioned). It may be valued at say $22, giving the trader an extra $2 per share profit compared to exercising the option. This $2 extra is the extrinsic value. We will study extrinsic value in detail later in the course.

Summary

In summary, exercising an option means exercising the right described in the contract, i.e. buying or selling the asset at the strike price. The right given to the buyer of a European option can only be exercised at expiration, whereas the right given to the buyer of an American option can be exercised at any time.

Closing an option position by buying or selling the option (thereby reducing the outstanding position to zero), is different to exercising the option. With both European and American style options, the option can be bought and sold freely before expiration. This means traders of both European and American style options are able to close or adjust their positions before expiration.

Lecture 2.4: Cash settled vs physically settled options

An option can be either physically settled or cash settled.

Physically settled option contracts

When a physically settled option contract is exercised, the asset is exchanged for the strike price given in the contract.

Let’s use our example from a previous lecture of a call option for stock XYZ with a strike price of $50, and let’s assume this contract is physically settled. When it is exercised, the option buyer is exercising their right to buy XYZ at $50 per share. As it is a physically settled contract, the option buyer receives the shares and must pay $50 per share for them.

This works similarly for physically settled put options. Imagine a put option for stock XYZ with a strike price of $45, and let’s assume this contract is physically settled. When it is exercised, the put option buyer is exercising their right to sell XYZ at $45 per share. As it is a physically settled contract, the put option buyer unloads their shares of XYZ and receives $45 per share for them.

Cash settled option contracts

When a cash settled option contract is exercised, it is only the difference between the strike price and the current price that is paid into the option buyer’s account. It is only the cash value of this difference that is paid, no shares (or other assets) are exchanged.

For example, let’s again assume a call option for stock XYZ with a strike price of $50, but this contract is cash settled instead. Let’s assume the current price of XYZ is $70, and the call option buyer exercises their right to buy the stock at $50 per share. As this contract is cash settled, it is just the difference between the current price ($70) and the strike price ($50) that is paid in cash to the buyer. In this case this would be $20 per share (which is calculated as $70 minus $50). So $20 per share is paid into the buyer’s account.

This works similarly for cash settled put options. Imagine a put option for stock XYZ with a strike price of $45, and that this put option is cash settled. Let’s assume the current price of XYZ has fallen to $30, and the put option buyer exercises their right to sell XYZ at $45 per share. As this contract is cash settled, it is just the difference between the strike price ($45) and the current price ($30) that is paid in cash to the put option buyer. In this case this would be $15 per share (which is calculated as $45 minus $30). So $15 per share is paid into the put option buyer’s accounts.

In summary

With physically settled options, the asset changes hands when an option is exercised. The asset is exchanged for the strike price defined in the option contract.

With cash settled options, the asset does not change hands when an option is exercised. It is the difference between the strike price and the current price that is paid to the option buyer. This is paid in cash into their trading account.

When we move on to the cryptocurrency options on Deribit in later sections, they will all be cash settled options.

Lecture 2.5: Option contract multiplier

Just one more parameter definition before we introduce you to some live option screens.

Remember in our previous examples we used a fictional stock XYZ, and defined the price and any payments on a per share basis. When trading options it is also important to understand how many shares (or how many units of the asset) an option contract represents.

This number is called the option contract multiplier. It can vary from product to product, but there are some common multipliers used across different groups of assets. No matter which exchange or product you are trading, this detail should be available in the contract details, but we’ll go through a couple of examples now.

Equity (stocks/shares) options typically have a multiplier of 100. This means that 1 option contract controls 100 shares of the underlying stock. Take the example of the physically settled call option from the previous lecture. The trader purchased a call option for stock XYZ with a strike price of $50. They then exercised their option to buy XYZ at $50 per share. The multiplier is 100, so this option contract controls 100 shares of XYZ. Therefore, when the trader exercises the option, they will pay $5,000 (which is calculated as the $50 strike price multiplied by the 100 multiplier), and they will receive 100 shares of XYZ.

The bitcoin options on Deribit have a multiplier of 1. This means that 1 option contract controls 1 bitcoin. Let’s say a trader holds 1 bitcoin call option with a strike price of $10,000. The bitcoin options on Deribit are European options, so they cannot be exercised early, and are exercised automatically when they expire. These options are also cash settled, which as you may remember from the previous lecture, means the difference between the current price and the strike price is what is paid in cash to the option buyer.

So, let’s assume this $10,000 call option expires when the price of bitcoin is $11,000. As it’s cash settled, the call option buyer receives the difference between the current price of $11,000 and the strike price of $10,000, which of course is $1,000. The multiplier is 1, so they receive $1,000 in total.

There will be plenty more examples detailing the exercising and closing of option positions later in the course, so don’t worry if you’re not completely comfortable with this concept yet.

When trading a new product, or on a new exchange, make sure you read any relevant documents. You should familiarise yourself with the contract details so you know how the products you’re planning to trade are structured. Before you begin trading options you should have an understanding of derivatives contracts and the basic option contract parameters. You should also know whether the options you’re planning to trade are European or American style options, physically or cash settled options, and the contract multiplier.

Well done for making it through these first definitions! It’s important to have this base level of knowledge to build on, but of course it’s difficult to learn everything about options just from definitions. There is so much to learn that gaining some practical experience along the way will help you retain the information. That doesn’t mean you have to put any funds at risk straight away, but it is useful to at least familiarise yourself with the trading platform you plan to use while you’re learning. With that in mind we will now take a look at some live option chains on several different exchanges. Being able to comfortably find your way around an option screen will speed up your learning as you progress.

Lecture 2.6: Option chains

One of the first things you will be greeted with when you start using an options platform, is an option chain. An option chain is a list of all available option contracts for a particular asset, grouped by expiry date. It will list both puts and calls, and all available strike prices for the given expiration.

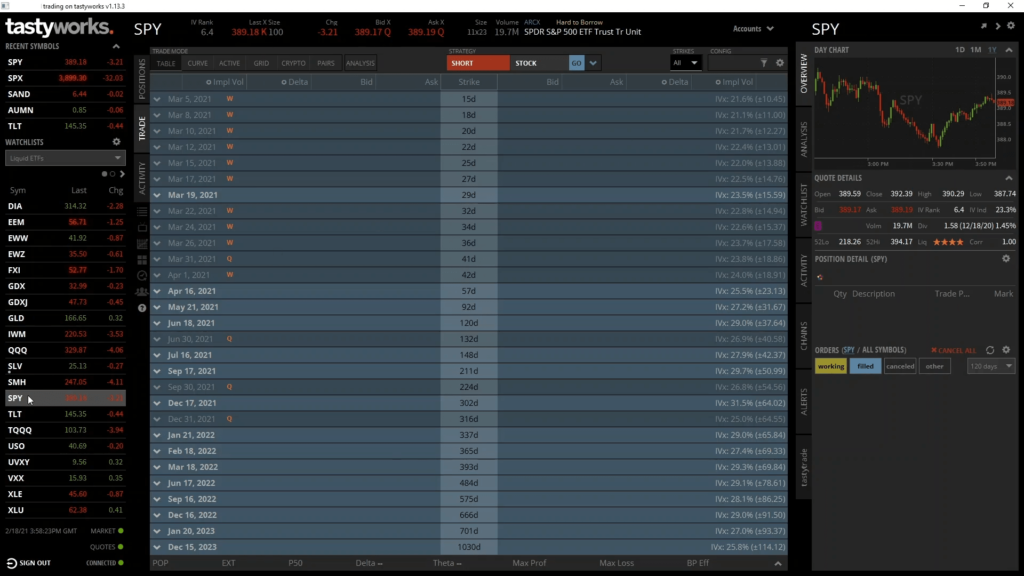

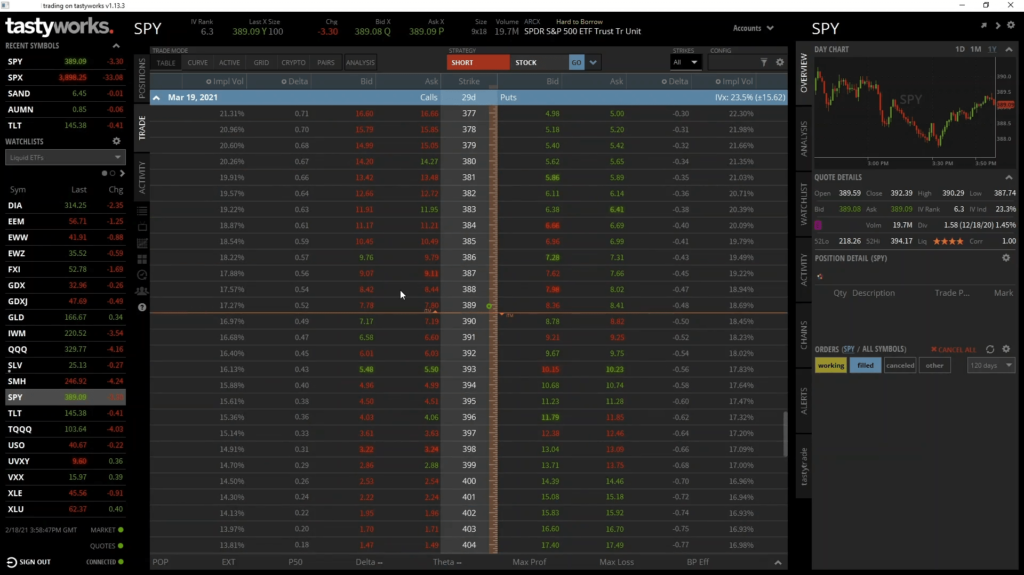

Tastyworks option chain

First let’s take a look at an option chain in the tastyworks desktop software. Tastyworks offer one of the most user friendly option interfaces I’ve seen, so it’s a great place to learn how an option chain is structured.

Let’s take a look at SPY, which is an ETF that tracks the US stock market, or the S&P 500 portion of the US stock market to be more precise. This is a very popular and liquid option market with many different expiry dates available.

To select SPY, we can type it into the search bar in the top right, or we can select it from one of our watchlists on the left. Once we’ve selected SPY the option chain will populate in the centre.

As you can see there are many different expiry dates displayed, but no options yet as each expiry date table is currently collapsed. To expand one or more we can click the little arrows like so.

This now shows every single option available for this expiry date. If this is your first time seeing an option chain it may be an overwhelming amount of numbers. In a few minutes you’ll know exactly what you’re looking at.

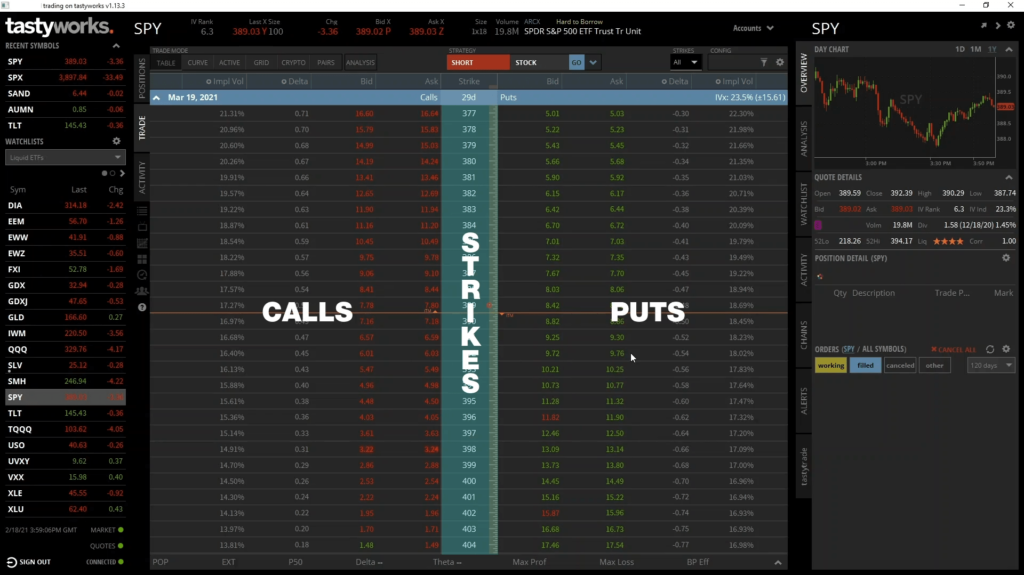

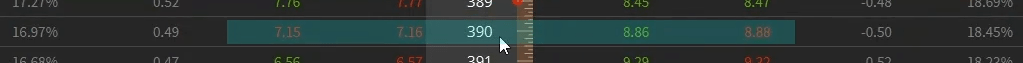

The most important thing you need to remember, and this is true across different platforms as well, is that the strike prices are displayed down the centre, with call options to the left, and put options to the right.

So that’s each of the available strike prices in the middle column, call options displayed to the left of this, and put options displayed to the right.

Each row has one call option with the strike price in the middle column, and one put option with the strike price in the middle column.

Let’s use this row as an example. We can see in the middle column that the strike price is $340. To the immediate left of this is the current best bid and ask prices for the $340 strike call option. To the immediate right of this is the current best bid and ask prices for the $340 put option.

We will cover bid and ask prices and the bid ask spread again later in the course, but the ask price is the price you can currently buy the option for, and the bid price is the price you can currently sell the option for.

There are lots of other statistics you can display for each option in the other columns, but the strike price column, bid/ask columns for calls, and bid/ask columns for puts, are the only ones that are essential to understand initially. For this reason, no matter what platform you are using, make sure you acquaint yourself with the location of each of these five columns, and then you’re already most of the way there to reading the option chain.

I also have it set to display the implied volatility and delta for each option in the extra columns. Both are topics we’ll cover in great detail later.

If we want to look at the options for a different expiry date, we can scroll up or down until we reach the one we are interested in. If we’re done with the current expiry date we can collapse it with the arrow, then find the one we want and expand that expiry date with the arrow on the left.

The same structure applies in each expiry date. Strike prices down the middle, call options on the left, and put options on the right.

We’ll be coming back to tastyworks later in the course to place some trades, but let’s now take a look at an option chain on another platform to see how it compares.

Interactive Brokers option chain

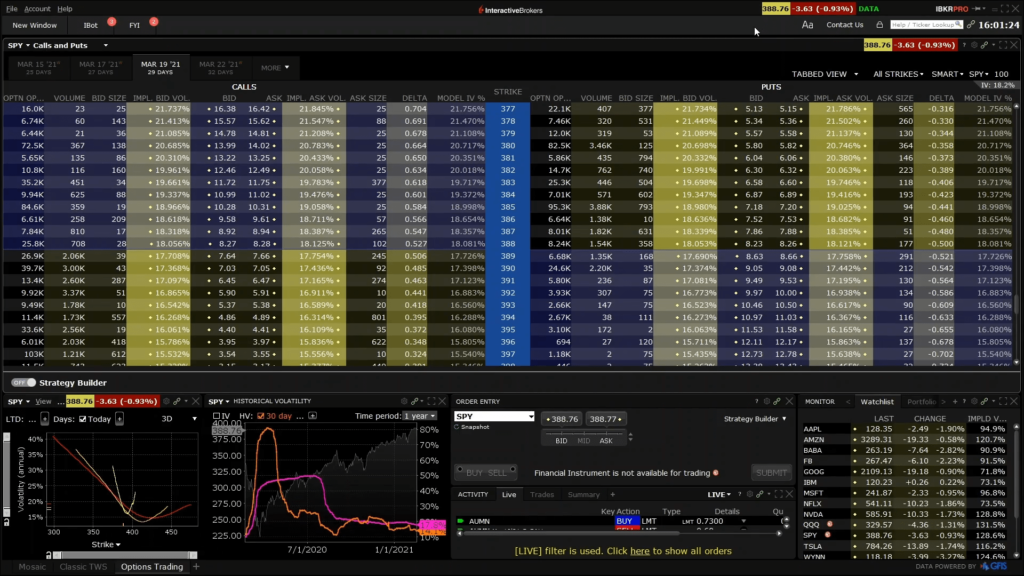

Here we have the Interactive Brokers desktop application, which is called Trader Workstation. Interactive Brokers software isn’t as pretty or user friendly as Tastyworks, but they do offer access to almost any market you can think of and are available in many countries.

We’ll look at the option chain for SPY again so it’s a like for like comparison. To display the option chain for SPY we can type SPY into the search function in the top right, press enter, then select the top result of SPY. As we are on the same product as before, all the options we look at here are exactly the same options we were looking at on Tastyworks, but displayed in the Interactive Brokers software instead.

Firstly, the main structure we emphasised previously is the same. Strike prices are displayed in this middle column, with calls on the left, and puts on the right.

I have a few more statistics displayed on Interactive Brokers, leading to a more cluttered screen, so let’s highlight the most important columns that we identified earlier, the bid and ask columns for each option.

As we mentioned we have strikes in the centre, and moving to the left we have the bid and ask for the call option at each strike price in these two columns. Moving over to the right, we have the bid and ask for the put option at each strike price in these two columns.

You can see each of the column headings at the top, and indeed this is very customisable on Interactive Brokers. If I just right click one of the column headings here and go to ‘Insert Column’ there are many different statistics that can be added. For now there is no need to know any of these. Just be sure you’re comfortable with finding the strike price, and bid and ask columns.

One difference you may have already spotted above the column headings is that the different expiry dates are displayed differently in Interactive Brokers than in Tastyworks. They are displayed as tabs above the option chain. If you want to select a different date you simply click the desired tab. If the one you are interested in is not shown, click ‘MORE’, and the other available dates will be shown in this menu. The SPY is a very popular product so there will always be lots of additional dates, but some smaller markets will have far fewer choices of expiry date. Some may not have any additional dates to the ones being displayed.

Again we will come back to Interactive Brokers for some live trade examples, but for now if you have an Interactive Brokers account, just have a quick practice of selecting a product, finding an expiry date, and then locating the strike price, bid columns and ask columns.

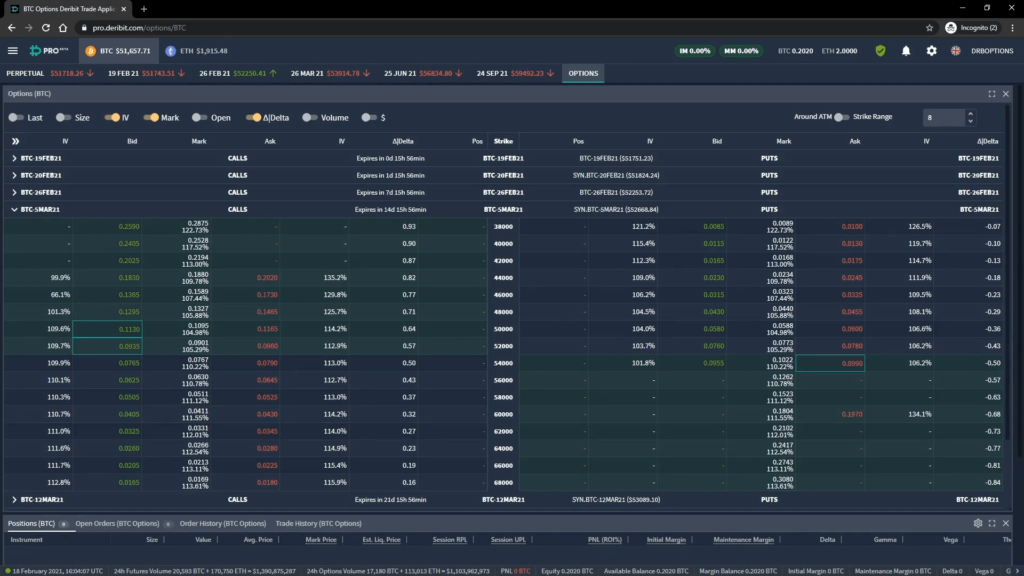

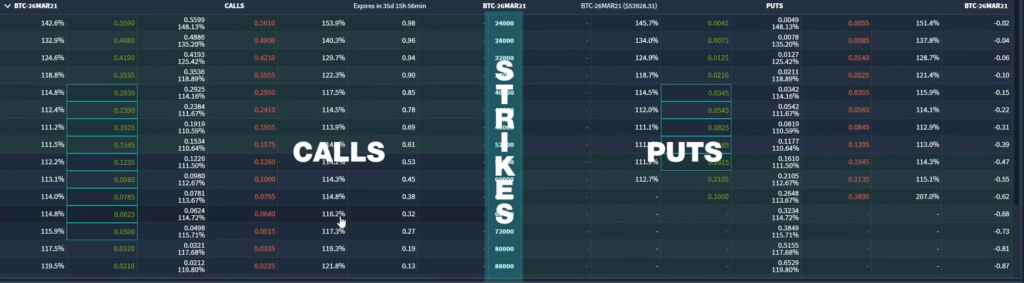

Deribit option chain

Finally let’s take a look at an option chain on Deribit. This is the Deribit pro UI, which is displayed in a browser here, rather than in a desktop application like the first two exchanges. We are currently looking at the bitcoin products, and to get to the options chain we just click ‘OPTIONS’ in the menu.

The layout of the Deribit options chain is similar to the Tastyworks option chain, in that the different expiry dates are displayed in a collapsible list on a single page. We can click one of the arrows to collapse or expand an expiry date.

As you can see, Deribit uses the same structure of strikes down the middle, calls on the left, and puts on the right. The bid and ask columns for calls can be found on the left, and the bid and ask columns for puts can be found on the right. On Deribit the bids are in green text and the asks are in red text, which helps your eye find things a little quicker.

To navigate to a different expiry date, we can scroll up or down, and of course we can collapse the date we’re currently looking at if we’re done with it.

As with the other platforms, there are also several other statistics that can be displayed in other columns. These can be enabled or disabled at the top of the option chain. We’ll be coming back to many of these extra statistics that are available later in the course.

Summary

You should now know what a typical option chain looks like, and how to navigate to the desired expiration date. Once you are looking at the desired date, you should then be able to find the list of strike prices, the bid and ask prices for calls, and the bid and ask prices for puts.

On most platforms you can also customise the option chain to suit your needs. You can do this by adding optional statistics that can be displayed in additional columns. These can include implied volatility, delta and other Greeks, open interest, volume and many others.

In the next section we will take a more detailed look at call options

Continue your learning: Proceed to Section 3